I Know the Plan I Have for You St. Louis Jesuits

"The Order of Jesus expelled from the Kingdom of Portugal by the Royal Prescript of 3 September 1759"; as a carrack sets sail from Portuguese shores in the background, a bolt of lightning strikes a Jesuit priest equally he attempts to set a terrestrial globe, a mitre, and a purple crown on fire; a pocketbook of gold coins and a airtight book (symbols of wealth and control of instruction) lie at the priest's anxiety.

The suppression of the Jesuits was the removal of all members of the Society of Jesus from near of the countries of Western Europe and their colonies beginning in 1759, and with the approving of the Holy See in 1773. The Jesuits were serially expelled from the Portuguese Empire (1759), France (1764), the Two Sicilies, Republic of malta, Parma, the Spanish Empire (1767) and Republic of austria and Republic of hungary (1782).

This timeline was influenced by political manoeuvrings both at Rome and within each country involved. The papacy reluctantly acceded to the anti-Jesuit demands of various Cosmic kingdoms while providing minimal theological justification for the suppressions.

Historians identify multiple factors causing the suppression. The Jesuits, who were not in a higher place getting involved in politics, were distrusted for their closeness to the pope and his ability in the religious and political diplomacy of independent nations. In French republic, information technology was a combination of many influences, from Jansenism to Free-thought, to the then prevailing impatience with the old club of things.[1] Monarchies attempting to centralise and secularise political power viewed the Jesuits as supranational, too strongly allied to the papacy, and too autonomous from the monarchs in whose territory they operated.[2]

With his Papal cursory, Dominus ac Redemptor (21 July 1773), Pope Clement XIV suppressed the Order every bit a fait accompli. Nonetheless, the social club did not disappear. Information technology continued underground operations in Red china, Russia, Prussia, and the United States. In Russia, Catherine the Dandy allowed the founding of a new novitiate.[3] In 1814, a subsequent Pope Pius Vii would act to restore the Jesuits Society to its previous provinces, and Jesuit cohorts began resuming their piece of work in those countries.[four]

Background to suppression [edit]

Prior to the eighteenth-century suppression of the Jesuits in many countries, there had been earlier bans, such as in territories of the Venetian Republic between 1606 and 1656–1657, begun and ended as role of disputes between the Republic and the Papacy, beginning with the Venetian Interdict.[five]

Past the mid-18th century, the Society had acquired a reputation in Europe for political maneuvering and economic success. Monarchs in many European states grew increasingly wary of what they saw as undue interference from a foreign entity. The expulsion of Jesuits from their states had the added benefit of allowing governments to impound the Society's accumulated wealth and possessions. However, historian Gibson (1966) cautions, "[h]ow far this served every bit a motive for the expulsion we practise not know."[half-dozen]

Various states took advantage of different events in order to take action. The series of political struggles between various monarchs, especially France and Portugal, began with disputes over territory in 1750 and culminated in the suspension of diplomatic relations and the dissolution of the Society by the Pope over most of Europe, and even some executions. The Portuguese Empire, France, the Ii Sicilies, Parma, and the Spanish Empire were involved to a different extent.

The conflicts began with trade disputes, in 1750 in Portugal, in 1755 in France, and in the late 1750s in the Two Sicilies. In 1758 the authorities of Joseph I of Portugal took advantage of the waning powers of Pope Bridegroom Fourteen and deported Jesuits from South America afterward relocating them with their native workers, so fighting a brief conflict, formally suppressing the order in 1759. In 1762 the Parlement Français (a courtroom, not a legislature) ruled against the Society in a huge bankruptcy case nether pressure from a host of groups – from within the Church but also secular notables such every bit Madame de Pompadour, the king'southward mistress. Austria and the Two Sicilies suppressed the order by prescript in 1767.

Lead-upwardly to suppression [edit]

First national suppression: Portugal and its empire in 1759 [edit]

There were long-standing tensions between the Portuguese crown and the Jesuits, which increased when the Count of Oeiras (later the Marquis of Pombal) became the monarch's government minister of land, culminating in the expulsion of the Jesuits in 1759. The Távora affair in 1758 could be considered a pretext for the expulsion and crown confiscation of Jesuit avails.[7] According to historians James Lockhart and Stuart B. Schwartz, the Jesuits' "independence, power, wealth, command of education, and ties to Rome made the Jesuits obvious targets for Pombal's brand of extreme regalism."[eight]

Portugal's quarrel with the Jesuits began over an exchange of South American colonial territory with Kingdom of spain. Past a underground treaty of 1750, Portugal relinquished to Spain the contested Colonia del Sacramento at the mouth of the Rio de la Plata in exchange for the Seven Reductions of Paraguay, the autonomous Jesuit missions that had been nominal Spanish colonial territory. The native Guaraní, who lived in the mission territories, were ordered to quit their country and settle across the Uruguay. Owing to the harsh conditions, the Guaraní rose in artillery against the transfer, and the so-called Guaraní War ensued. Information technology was a disaster for the Guaraní. In Portugal, a battle escalated, with inflammatory pamphlets denouncing or defending the Jesuits, who, for over a century, had protected the Guarani from enslavement through a network of Reductions, every bit depicted in The Mission. The Portuguese colonizers secured the expulsion of the Jesuits.[9] [10]

On 1 April 1758, Pombal persuaded the aged Pope Bridegroom XIV to appoint the Portuguese Cardinal Saldanha to investigate allegations against the Jesuits.[11] Benedict was skeptical as to the gravity of the alleged abuses. He ordered a "minute enquiry", but, so equally to safeguard the reputation of the Society, all serious matters were to be referred back to him. Benedict died the following month on May 3. On May fifteen, Saldanha, having received the papal brief only a fortnight before, declared that the Jesuits were guilty of having exercised "illicit, public, and scandalous commerce," both in Portugal and in its colonies. He had non visited Jesuit houses equally ordered and pronounced on the issues which the pope had reserved to himself.[x]

Pombal implicated the Jesuits in the Távora affair, an attempted assassination of the rex on 3 September 1758, on the grounds of their friendship with some of the supposed conspirators. On nineteen January 1759, he issued a decree sequestering the holding of the Society in the Portuguese dominions and the following September deported the Portuguese fathers, about one thousand in number, to the Pontifical States, keeping the foreigners in prison. Amidst those arrested and executed was the then denounced Gabriel Malagrida, the Jesuit confessor of Leonor of Távora, for "crimes against the religion". After Malagrida'due south execution in 1759, the Social club was suppressed past the Portuguese crown. The Portuguese ambassador was recalled from Rome and the papal nuncio expelled. Diplomatic relations between Portugal and Rome were broken off until 1770.[11]

Suppression in France in 1764 [edit]

The suppression of the Jesuits in France began in the French island colony of Martinique, where the Society of Jesus had a commercial stake in sugar plantations worked by black slave and costless labor. Their big mission plantations included big local populations that worked under the usual weather condition of tropical colonial agriculture of the 18th century. The Catholic Encyclopedia in 1908 said that the practise of the missionaries occupying themselves personally in selling off the appurtenances produced (an anomaly for a religious order) "was allowed partly to provide for the current expenses of the mission, partly in guild to protect the simple, childlike natives from the mutual plague of dishonest intermediaries."[ commendation needed ]

Male parent Antoine La Vallette, Superior of the Martinique missions, borrowed coin to expand the big undeveloped resources of the colony. But on the outbreak of war with England, ships conveying goods of an estimated value of 2,000,000 livres were captured, and La Vallette of a sudden went broke for a very large sum. His creditors turned to the Jesuit procurator in Paris to need payment, just he refused responsibility for the debts of an independent mission – though he offered to negotiate for a settlement. The creditors went to the courts and received a favorable decision in 1760, obliging the Gild to pay and giving leave to distrain in the instance of non-payment. The Jesuits, on the advice of their lawyers, appealed to the Parlement of Paris. This turned out to be an imprudent step for their interests. Non simply did the Parlement support the lower courtroom on viii May 1761, but having once gotten the example into its easily, the Jesuits' opponents in that assembly determined to strike a blow at the Order.

The Jesuits had many who opposed them. The Jansenists were numerous amid the enemies of the orthodox party. The Sorbonne, an educational rival, joined the Gallicans, the Philosophes, and the Encyclopédistes. Louis 15 was weak; his married woman and children were in favor of the Jesuits; his able first minister, the Duc de Choiseul, played into the hands of the Parlement and the regal mistress, Madame de Pompadour, to whom the Jesuits had refused absolution for she was living in sin with the Rex of French republic, was a adamant opponent. The determination of the Parlement of Paris in time bore downwardly all opposition.

The attack on the Jesuits was opened on 17 April 1762 by the Jansenist sympathizer the Abbé Chauvelin, who denounced the Constitution of the Social club of Jesus, which was publicly examined and discussed in a hostile printing. The Parlement issued its Extraits des assertions assembled from passages from Jesuit theologians and canonists, in which they were alleged to teach every sort of immorality and error. On 6 August 1762, the terminal arrêt was proposed to the Parlement by the Abet Full general Joly de Fleury, condemning the Guild to extinction, only the king's intervention brought viii months' delay, and in the meantime a compromise was suggested by the Courtroom. If the French Jesuits would carve up from the Society headed past the Jesuit General directly nether the pope'south say-so and come under a French vicar, with French customs, as with the Gallican Church, the Crown would nonetheless protect them. The French Jesuits, rejecting Gallicanism, refused to consent. On i April 1763, the colleges were closed, and by a further arrêt of March 9, 1764, the Jesuits were required to renounce their vows under pain of adjournment. At the end of Nov 1764, the king signed an edict dissolving the Society throughout his dominions, for they were still protected by some provincial parlements, as in Franche-Comté, Alsace, and Artois. In the draft of the edict, he canceled numerous clauses that implied that the Social club was guilty, and writing to Choiseul he concluded: "If I adopt the advice of others for the peace of my realm, y'all must make the changes I propose, or I volition do null. I say no more, lest I should say too much."[12]

Decline of the Jesuits in New France [edit]

Following the British 1759 victory confronting the French in Quebec, France lost its Due north American territory of New France, where Jesuit missionaries in the seventeenth century had been active among ethnic peoples. British dominion had implications for Jesuits in New France, but their numbers and sites were already in decline. Equally early on every bit 1700, the Jesuits had adopted a policy of just maintaining their existing posts, instead of trying to establish new ones across Quebec, Montreal, and Ottawa.[13] Once New France was under British command, the British barred the immigration of any farther Jesuits. Past 1763, there were only twenty-one Jesuits notwithstanding stationed in what was now the British colony of Quebec. By 1773, merely eleven Jesuits remained. In the same year, the British crown laid claim to Jesuit belongings in Canada and declared that the Society of Jesus in New French republic was dissolved.[14]

Castilian Empire suppression of 1767 [edit]

Events leading to the Spanish suppression [edit]

Charles III of Spain, who ordered the expulsion of the Jesuits from Castilian realms

The Suppression in Spain and in the Spanish colonies, and in its dependency the Kingdom of Naples, was the last of the expulsions, with Portugal (1759) and France (1764) having already set the pattern. The Spanish crown had already begun a serial of authoritative and other changes in their overseas empire, such as reorganizing the viceroyalties, rethinking economical policies, and establishing a military, then that the expulsion of the Jesuits is seen as part of this general trend known by and large equally the Bourbon Reforms. The aim of the reforms was to adjourn the increasing autonomy and self-confidence of American-born Spaniards, reassert crown control, and increase revenues.[fifteen] Some historians doubt that the Jesuits were guilty of intrigues confronting the Spanish crown that were used equally the firsthand cause for the expulsion.[16]

Contemporaries in Spain attributed the suppression of the Jesuits to the Esquilache Riots, named afterwards the Italian counselor to Bourbon king Carlos Iii, that erupted later a sumptuary law was enacted. The constabulary, placing restrictions on men's wearing of voluminous capes and limiting the breadth of sombreros the men could wear, was seen as an "insult to Castilian pride."[17]

When an angry crowd of those resisters converged on the purple palace, king Carlos fled to the countryside. The crowd had shouted "Long Live Spain! Death to Esquilache!" His Flemish palace baby-sit fired warning shots over the people's heads. An account says that a group of Jesuit priests appeared on the scene, soothed the protesters with speeches, and sent them home. Carlos decided to rescind the tax hike and hat-trimming edict and to burn down his finance minister.[18]

The monarch and his advisers were alarmed by the uprising, which challenged royal dominance, and the Jesuits were accused of inciting the mob and publicly accusing the monarch of religious crimes. Pedro Rodríguez de Campomanes, attorney for the Council of Castile, the body overseeing key Spain, articulated this view in a study the male monarch read.[19] Charles Iii ordered the convening of a special regal commission to draw up a master plan to expel the Jesuits. The commission starting time met in January 1767. It modeled its plan on the tactics deployed by France'south Philip IV against the Knights Templar in 1307 – emphasizing the element of surprise.[20] Charles'south adviser Campomanes had written a treatise on the Templars in 1747, which may have informed the implementation of the Jesuit suppression.[21] Ane historian states that "Charles III never would accept dared to expel the Jesuits had he not been assured of the support of an influential party within the Spanish Church."[xix] Jansenists and mendicant orders had long opposed the Jesuits and sought to curtail their power.

Secret plan of expulsion [edit]

Manuel de Roda, adviser to Charles Iii, who brought together an alliance of those opposed to the Jesuits

King Charles's ministers kept their deliberations to themselves, as did the king, who acted upon "urgent, merely, and necessary reasons, which I reserve in my purple listen." The correspondence of Bernardo Tanucci, Charles's anti-clerical minister in Naples, contains the ideas which, from time to time, guided Castilian policy. Charles conducted his regime through the Count of Aranda, a reader of Voltaire, and other liberals.[12]

The commission's meeting on 29 January 1767 planned the expulsion of the Jesuits. Undercover orders, to be opened at sunrise on Apr 2, were sent to all provincial viceroys and district armed forces commanders in Spain. Each sealed envelope independent two documents. One was a copy of the original order expelling "all members of the Society of Jesus" from Charles's Spanish domains and confiscating all their appurtenances. The other instructed local officials to surround the Jesuit colleges and residences on the dark of April two, abort the Jesuits, and adapt their passage to ships awaiting them at diverse ports. King Carlos' closing sentence read: "If a unmarried Jesuit, even though ill or dying, is still to exist establish in the area under your command after the embarkation, ready yourself to face summary execution."[22]

Pope Clement Xiii, presented with a similar ultimatum past the Spanish ambassador to the Vatican a few days before the decree would accept effect, asked King Charles "by what authority?" and threatened him with eternal damnation. Pope Clement had no means to enforce his protestation and the expulsion took place as planned.[23]

Jesuits expelled from Mexico (New Spain) [edit]

José de Gálvez, Visitador generál in New Kingdom of spain (1765–71), was instrumental in the Jesuit expulsion in 1767 in United mexican states, considered part of the Bourbon Reforms.

In New Spain, the Jesuits had actively evangelized the Indians on the northern frontier. But their main activity involved educating elite criollo (American-born Spanish) men, many of whom themselves became Jesuits. Of the 678 Jesuits expelled from Mexico, 75% were Mexican-born. In tardily June 1767, Spanish soldiers removed the Jesuits from their xvi missions and 32 stations in United mexican states. No Jesuit, no thing how old or ill, could be excepted from the rex's prescript. Many died on the trek along the cactus-studded trail to the Gulf Coast port of Veracruz, where ships awaited them to transport them to Italian exile.[24]

At that place were protests in United mexican states at the exile of so many Jesuit members of elite families. Merely the Jesuits themselves obeyed the order. Since the Jesuits had owned all-encompassing landed estates in United mexican states – which supported both their evangelization of indigenous peoples and their education mission to criollo elites – the properties became a source of wealth for the crown. The crown auctioned them off, benefiting the treasury, and their criollo purchasers gained productive well-run properties.[25] [26] Many criollo families felt outraged at the crown's actions, regarding it as a "despotic human activity."[27] One well-known Mexican Jesuit, Francisco Javier Clavijero, during his Italian exile wrote an important history of Mexico, with emphasis on the indigenous peoples.[28] Alexander von Humboldt, the famous German language scientist who spent a year in Mexico in 1803–04, praised Clavijero'south piece of work on the history of Mexico's indigenous peoples.[29]

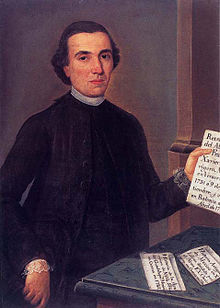

Francisco Javier Clavijero, Mexican Jesuit exiled to Italy. His history of aboriginal Mexico was a significant text for pride for contemporaries in New Spain. He is revered in modern Mexico as a creole patriot.

Due to the isolation of the Spanish missions on the Baja California peninsula, the expulsion decree did non arrive in Baja California in June 1767, as in the rest of New Spain. Information technology got delayed until the new governor, Gaspar de Portolá, arrived with the news and decree on November 30. Past three Feb 1768, Portolá's soldiers had removed the peninsula'south 16 Jesuit missionaries from their posts and gathered them in Loreto, whence they sailed to the Mexican mainland and thence to Europe. Showing sympathy for the Jesuits, Portolá treated them kindly, fifty-fifty as he put an end to their 70 years of mission-building in Baja California.[30] The Jesuit missions in Baja California were turned over to the Franciscans and subsequently to the Dominicans, and the future missions in Alta California were founded by Franciscans.[31]

The change in the Spanish colonies in the New Globe was particularly peachy, as the far-flung settlements were often dominated by missions. Almost overnight, in the mission towns of Sonora and Arizona, the "black robes" (Jesuits) disappeared and the "gray robes" (Franciscans) replaced them.[32]

Expulsion from the Philippines [edit]

The royal decree expelling the Order of Jesus from Kingdom of spain and its dominions reached Manila on 17 May 1768. Between 1769 and 1771, the Jesuits were transported from the Castilian E Indies to Kingdom of spain and from there deported to Italian republic.[33]

Exile of Spanish Jesuits to Italia [edit]

Bernardo Tanucci, adviser to Charles Iii, instrumental in the expulsion of the Jesuits in Naples

Spanish soldiers rounded upwardly the Jesuits in Mexico, marched them to the coasts, and placed them below the decks of Spanish warships headed for the Italian port of Civitavecchia in the Papal States. When they arrived, Pope Clement 13 refused to allow the ships to unload their prisoners onto papal territory. Fired upon past batteries of arms from the shore of Civitavecchia, the Castilian warships had to wait for an anchorage off the island of Corsica, and then a dependency of Genoa. But since a rebellion had erupted on Corsica, information technology took five months earlier some of the Jesuits could set foot on country.[12]

Several historians have estimated the number of Jesuits deported at half-dozen,000. Simply information technology is non articulate whether this figure encompasses Spain solitary or extends to Espana'south overseas colonies (notably Mexico and the Philippines) as well.[34] Jesuit historian Hubert Becher claims that about 600 Jesuits died during their voyage and waiting ordeal.[35]

In Naples, male monarch Carlos' minister Bernardo Tanucci pursued a similar policy: On November 3, the Jesuits, with no accusation or trial, were marched across the border into the Papal States and threatened with death if they returned.[10]

Historian Charles Gibson calls the Castilian crown'due south expulsion of the Jesuits a "sudden and devastating move" to affirm royal command.[25] Notwithstanding, the Jesuits became a vulnerable target for the crown's moves to assert more control over the church; as well some religious and diocesan clergy and civil regime were hostile to them, and they did non protest their expulsion.[36]

In addition to 1767, the Jesuits were suppressed and banned twice more in Espana, in 1834 and in 1932. Spanish ruler Francisco Franco rescinded the last suppression in 1938.[ citation needed ]

Economic impact in the Spanish Empire [edit]

The suppression of the order had longstanding economical furnishings in the Americas, particularly those areas where they had their missions or reductions – outlying areas dominated by indigenous peoples such as Paraguay and Chiloé Archipelago. In Misiones, in modernistic-twenty-four hours Argentina, their suppression led to the scattering and enslavement of indigenous Guaranís living in the reductions and a long-term decline in the yerba mate industry, from which it simply recovered in the 20th century.[37]

With the suppression of the Club of Jesus in Castilian America, Jesuit vineyards in Peru were auctioned, but new owners did not take the aforementioned expertise as the Jesuits, contributing to a turn down in production of wine and pisco.[38]

Suppression in Malta [edit]

Republic of malta was at the time a vassal of the Kingdom of Sicily, and Grandmaster Manuel Pinto da Fonseca, himself a Portuguese, followed suit, expelling the Jesuits from the island and seizing their assets. These assets were used in establishing the University of Malta past a decree signed by Pinto on 22 November 1769, with lasting issue on the social and cultural life of Malta.[39] The Church of the Jesuits (in Maltese Knisja tal-Ġiżwiti ), one of the oldest churches in Valletta, retains this proper name upwards to the present.

Expulsion from the Duchy of Parma [edit]

The independent Duchy of Parma was the smallest Bourbon court. So ambitious in its anti-clericalism was the Parmesan reaction to the news of the expulsion of the Jesuits from Naples, that Pope Clement XIII addressed a public alert against information technology on 30 January 1768, threatening the Duchy with ecclesiastical censures. At this, all the Bourbon courts turned against the Holy See, demanding the unabridged dissolution of the Jesuits. Parma expelled the Jesuits from its territories, confiscating their possessions.[12]

Dissolution in Poland and Lithuania [edit]

The Jesuit order was disbanded in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1773. However, in the territories occupied by the Russian Empire in the First Sectionalisation of Poland the Gild was not disbanded, as Russian Empress Catherine dismissed the Papal social club.[40] In the Commonwealth, many of the Order's possessions were taken over by the Committee of National Education, the world's showtime Ministry of Education. Lithuania complied with the suppression.[41]

Papal suppression of 1773 [edit]

Later on the suppression of the Jesuits in many European countries and their overseas empires, Pope Clement Xiv issued a papal brief on 21 July 1773, in Rome titled: Dominus ac Redemptor Noster. That decree included the following statement.

Having farther considered that the said Visitor of Jesus can no longer produce those arable fruits...in the present example, we are determining upon the fate of a order classed among the mendicant orders, both past its institute and by its privileges; after a mature deliberation, we do, out of our certain knowledge, and the fullness of our apostolical power, suppress and abolish the said company: we deprive it of all activity whatever... And to this finish a fellow member of the regular clergy, recommendable for his prudence and sound morals, shall be called to preside over and govern the said houses; so that the proper noun of the Company shall be, and is, for ever extinguished and suppressed.

—Pope Clement XIV, Dominus air-conditioning Redemptor Noster [42]

Resistance in Belgium [edit]

Later papal suppression in 1773, the scholarly Jesuit Society of Bollandists moved from Antwerp to Brussels, where they continued their work in the monastery of the Coudenberg; in 1788, the Bollandist Guild was suppressed by the Austrian government of the Low Countries.[43]

Continued Jesuit work in Prussia [edit]

Frederick the Great of Prussia refused to permit the papal document of suppression to be distributed in his land.[44] The society continued in Prussia for several years after the suppression, although it had dissolved before the 1814 restoration.

Continued piece of work in North America [edit]

Many private Jesuits continued their work as Jesuits in Quebec, although the concluding 1 died in 1800. The 21 Jesuits living in North America signed a document offering their submission to Rome in 1774.[45] In the United states of america, schools and colleges connected to be run and founded by Jesuits.[44]

Russian resistance to suppression [edit]

In Imperial Russia, Catherine the Great refused to allow the papal certificate of suppression to exist distributed and fifty-fifty openly defended the Jesuits from dissolution, and the Jesuit chapter in Republic of belarus received her patronage. It ordained priests, operated schools, and opened housing for novitiates and tertianships. Catherine's successor, Paul I, successfully asked Pope Pius Seven in 1801 for formal approval of the Jesuit functioning in Russia. The Jesuits, led first by Gabriel Gruber and after his death by Tadeusz Brzozowski, continued to expand in Russia under Alexander I, adding missions and schools in Astrakhan, Moscow, Riga, Saratov, and St. petersburg and throughout the Caucasus and Siberia. Many former Jesuits throughout Europe traveled to Russian federation to join the sanctioned guild at that place.[46]

Alexander I withdrew his patronage of the Jesuits in 1812, just with the restoration of the Order in 1814, that had just a temporary event on the order. Alexander eventually expelled all Jesuits from Imperial Russia in March 1820.[40] [41] [47]

Russian patronage of restoration in Europe and North America [edit]

Under the patronage of the "Russian Society", Jesuit provinces were effectively reconstituted in the Kingdom of Great Great britain in 1803, the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies in 1803, and the United states in 1805.[46] "Russian" capacity were also formed in Kingdom of belgium, Italy, holland, and Switzerland.[48]

Acquiescence in Austria and Hungary [edit]

The Secularization Prescript of Joseph Two (Holy Roman Emperor from 1765 to 1790 and ruler of the Habsburg lands from 1780 to 1790) issued on 12 Jan 1782 for Austria and Hungary banned several monastic orders non involved in teaching or healing and liquidated 140 monasteries (domicile to 1484 monks and 190 nuns). The banned monastic orders included Jesuits, Camaldolese, Order of Friars Pocket-size Capuchin, Carmelites, Carthusians, Poor Clares, Lodge of Saint Bridegroom, Cistercians, Dominican Order (Order of Preachers), Franciscans, Pauline Fathers and Premonstratensians, and their wealth was taken over by the Religious Fund.

His anticlerical and liberal innovations induced Pope Pius Half-dozen to pay Joseph II a visit in March 1782. He received the Pope politely and presented himself as a good Catholic, just refused to be influenced.

Restoration of the Jesuits [edit]

As the Napoleonic Wars were approaching their cease in 1814, the old political society of Europe was to a considerable extent restored at the Congress of Vienna after years of fighting and revolution, during which the Church had been persecuted every bit an agent of the sometime order and abused under the rule of Napoleon. With the political climate of Europe changed, and with the powerful monarchs who had called for the suppression of the Society no longer in power, Pope Pius VII issued an order restoring the Lodge of Jesus in the Catholic countries of Europe. For its part, the Society of Jesus made the decision at the first General Congregation held after the restoration to keep the organization of the Society the way that it had been before the suppression was ordered in 1773.

Later 1815, with the Restoration, the Catholic Church building began to play a more welcome role in European political life once once more. Nation by nation, the Jesuits became re-established.

The mod view is that the suppression of the society was the event of a series of political and economical conflicts rather than a theological controversy, and the assertion of nation-land independence confronting the Catholic Church. The expulsion of the Order of Jesus from the Catholic nations of Europe and their colonial empires is also seen as one of the early manifestations of the new secularist zeitgeist of the Enlightenment.[49] It peaked with the anti-clericalism of the French Revolution. The suppression was too seen as beingness an endeavour by monarchs to gain command of revenues and trade that were previously dominated by the Society of Jesus. Catholic historians oft point to a personal conflict betwixt Pope Clement XIII (1758–1769) and his supporters within the church and the crown cardinals backed by French republic.[10]

See also [edit]

- Society of the Faith of Jesus

References [edit]

- ^ Roehner, Bertrand M. (April 1997), "Jesuits and the State: A Comparative Study of their Expulsions (1590–1990)", Religion, 27 (2): 165–182, doi:10.1006/reli.1996.0048

- ^ Ida Altman et al., The Early History of Greater Mexico, Pearson 2003, p. 310.

- ^ Keen Events in Religion. Denver: ABC-CLIO. 2017. p. 812. ISBN9781440845994.

- ^ "Catholic ENCYCLOPEDIA: The Restored Jesuits (1814-1912)". world wide web.newadvent.org . Retrieved 2017-03-21 .

- ^ Gerbino, Giuseppe (June 2008). "Review of Muir, Edward The Culture Wars of the Late Renaissance: Skeptics, libertines, and opera". H-Italy (volume review). H-Cyberspace Reviews;

the reviewed book is

Muir, Edward (2007). The Civilization Wars of the Late Renaissance: Skeptics, libertines, and opera. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN978-0-674-02481-6. - ^ Gibson, Charles (1966). Spain in America. New York, NY: Harper and Row. p. 83, footnote [28].

- ^ James Lockhart and Stuart B. Schwartz, Early Latin America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Printing 1983, p. 391.

- ^ Lockhart and Schwartz, Early Latin America, p. 391.

- ^ Ganson, Barbara (2003). The Guarani under Spanish Rule in the Rio de la Plata. Stanford University Press. ISBN978-0-8047-5495-8.

- ^ a b c d Pollen, John Hungerford. "The Suppression of the Jesuits (1750-1773)" The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 14. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1912. 26 March 2014

This commodity incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain .

This commodity incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain . - ^ a b Prestage, Edgar. "Marquis de Pombal" The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 12. New York: Robert Appleton Visitor, 1911. 26 March 2014

- ^ a b c d Vogel, Christine: The Suppression of the Society of Jesus, 1758–1773, European History Online, Mainz: Institute of European History, 2011, retrieved: November 11, 2011.

- ^ J.H. Kennedy. Jesuit and Roughshod in New France (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1950), 49.

- ^ J.H. Kennedy. Jesuit and Cruel in New France (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1950), 53.

- ^ Virginia Guedea, "The Old Colonialism Ends, the New Colonialism Begins", in The Oxford History of Mexico, edited by Michael Meyer and William Beezley, New York: Oxford University Printing 2000, p278..

- ^ James Lockhart and Stuart Schwartz, Early Latin America, New York: Cambridge Academy Press 1983, p. 350.

- ^ D.A. Brading, The Beginning America: The Spanish Monarchy, Creole Patriots, and the Liberal State, 1492-1867. Cambridge: Cambridge University Printing 1991, 499.

- ^ Manfred Barthel. The Jesuits: History and Fable of the Society of Jesus. Translated and adjusted from the German by Marker Howson. William Morrow & Co., 1984, pp. 222-3.

- ^ a b D.A. Brading, The Get-go America, p. 499.

- ^ Manfred Barthel. The Jesuits: History and Fable of the Society of Jesus. Translated and adapted from the German past Marking Howson. William Morrow & Co., 1984, p. 223.

- ^ Pedro Rodríguez de Campomanes, Dissertaciones históricas del orden, y Cavallería de los templarios, o resumen historial de sus principios, fundación, instituto, progressos, y extinción en el Concilio de Viena. Y united nations apéndice, o suplemento, en que se pone la regla de esta orden, y diferentes Privilegios de ella, con muchas Dissertaciones, y Notas, tocantes no solo à esta Orden, sino à las de S. Juan, Teutonicos, Santiago, Calatrava, Alcantara, Avis, Montesa, Christo, Monfrac, y otras Iglesias, y Monasterios de España, con varios Cathalogos de Maestres. Madrid: Oficina de Antonio Pérez de Soto.

- ^ Manfred Barthel. The Jesuits: History and Legend of the Society of Jesus. Translated and adapted from the German by Marker Howson. William Morrow & Co., 1984, pp. 223-4.

- ^ Manfred Barthel. The Jesuits: History and Fable of the Gild of Jesus. Translated and adapted from the German language by Mark Howson. William Morrow & Co., 1984, pp. 224-6.

- ^ Don DeNevi and Noel Francis Moholy. Junípero Serra: The Illustrated Story of the Franciscan Founder of California's Missions. Harper & Row, 1985, p. 7.

- ^ a b Charles Gibson, Kingdom of spain in America, New York: Harper and Row, p.83-84.

- ^ Ida Altman et al., The Early History of Greater Mexico, Pearson 2003, pp. 310-eleven.

- ^ Susan Deans-Smith, "Bourbon Reforms", Encyclopedia of Mexico: History, Society, Civilisation, volume 1. Michael South. Werner, ed., Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997, pp. 153-154.

- ^ D.A. Brading, The First America: The Spanish Monarchy, Creole Patriots, and the Liberal State, 1492-1867. Cambridge: Cambridge University Printing 1991, pp. 453-58.

- ^ D.A. Brading, The Kickoff America, pp. 523-24, 526-seven.

- ^ Maynard Geiger. The Life and Times of Fray Junípero Serra: The Man Who Never Turned Dorsum. Academy of American Franciscan History, 1959, vol. 1, pp. 182-3.

- ^ Robert Michael Van Handel, "The Jesuit and Franciscan Missions in Baja California." Thou.A. thesis. University of California, Santa Barbara, 1991.

- ^ Pourade, Richard F. (2014). "6: Padres Atomic number 82 the Way". The History of San Diego . Retrieved 20 February 2014.

- ^ de la Costa, Horacio (2014). "Jesuits in the Philippines: From Mission to Province (1581-1768)". Philippine Jesuits . Retrieved 20 February 2014.

- ^ Manfred Barthel. The Jesuits: History and Legend of the Order of Jesus. Translated and adapted from the German past Marker Howson. William Morrow & Co., 1984, p. 225, footnote.

- ^ Hubert Becher, SJ. Die Jesuiten: Gestalt und Geschichte des Ordens. Munich, 1951.

- ^ Clarence Haring, The Spanish Empire in America, Oxford University Press, 1947, p. 206.

- ^ Daumas, Ernesto (1930). El problema de la yerba mate (in Spanish). Buenos Aires: Compañia Impresora Argentine republic.

- ^ Lacoste, Pablo (2004). "La vid y el wine en América del Sur: el desplazamiento de los polos vitivinícolas (siglos XVI al Xx)". Universum (in Castilian). 19 (2). doi:10.4067/S0718-23762004000200005.

- ^ "History of the Academy". University of Malta. 2014. Archived from the original on 30 June 2011. Retrieved 20 Feb 2014.

- ^ a b "Kasata Zakonu" [Abolishment Order]. Social club of Jesus in Poland (in Polish). 2014. Retrieved 20 February 2014.

- ^ a b Grzebień, Ludwik (2014). "Wskrzeszenie zakonu jezuitów" [The Resurrection of the Jesuits]. mateusz.pl (in Smoothen). Retrieved 20 February 2014.

- ^ Pope Cloudless Xiv. "Dominus ac Redemptor (1773)". Boston Higher, Institute for Avant-garde Jesuit Studies.

- ^ "The Bollandist Acta Sanctorum", Catholic World, Volume 28, Effect 163, October 1878; p. 81

- ^ a b Casalini 2017, p. 162.

- ^ Schlafly 2015, p. 201.

- ^ a b Schlafly 2015, p. 202.

- ^ Schlafly 2015, pp. 202–203.

- ^ Maryks & Wright 2015, p. 3.

- ^ "Lodge Restored: Remembering turbulent times for the Jesuits". America Magazine. 2014-07-22. Retrieved 2017-03-21 .

Bibliography [edit]

- Casalini, Cristiano (2017). "Rise, Graphic symbol, and Evolution of Jesuit Education". In Županov, Ines M. (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Jesuits. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN9780190639631.

- Maryks, Robert A.; Wright, Jonathan (2015). "Introduction". In Maryks, Robert A.; Wright, Jonathan (eds.). Jesuit Survival and Restoration: A Global History, 1773-1900. Boston: Brill. ISBN9789004282384.

- Schlafly, Daniel Fifty. Jr. (2015). "Full general Repression, Russian Survival, American Success: The 'Russian' Society of Jesus and the Jesuits in the Usa". In Burson, Jeffrey D. (ed.). The Jesuit Suppression in Global Context: Causes, Events, and Consequences. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN9781107030589.

Farther reading [edit]

- Chadwick, Owen (1981). The Popes and European Revolution. Clarendon Press. pp. 346–91. ISBN9780198269199. also online

- Cummins, J. S. "The Suppression of the Jesuits, 1773" History Today (Dec 1973), Vol. 23 Issue 12, pp 839–848, online; popular business relationship.

- Schroth, Raymond A. "Expiry and Resurrection: The Suppression of the Jesuits in N America." American Cosmic Studies 128.1 (2017): 51–66.

- Van Kley, Dale. The Jansenists and the Expulsion of the Jesuits from France (Yale Up, 1975).

- Van Kley, Dale K. Reform Catholicism and the international suppression of the Jesuits in Enlightenment Europe (Yale Upwards, 2018); online review

- Wright, Jonathan, and Jeffrey D Burson. The Jesuit Suppression in Global Context: Causes, Events, and Consequences. Cambridge University Press, 2015.

External links [edit]

-

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain:Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "The Suppression of the Jesuits (1750-1773)". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain:Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "The Suppression of the Jesuits (1750-1773)". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. - Charles 3 of Spain's royal decree expelling the Jesuits

- Vogel, Christine: The Suppression of the Society of Jesus, 1758–1773, European History Online, Mainz: Constitute of European History, 2011, retrieved: November 11, 2011.

- The Decease of a Weak and Regretful Pope: September 22, 1774 at Catholic Text Volume Projection

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Suppression_of_the_Society_of_Jesus

0 Response to "I Know the Plan I Have for You St. Louis Jesuits"

Post a Comment